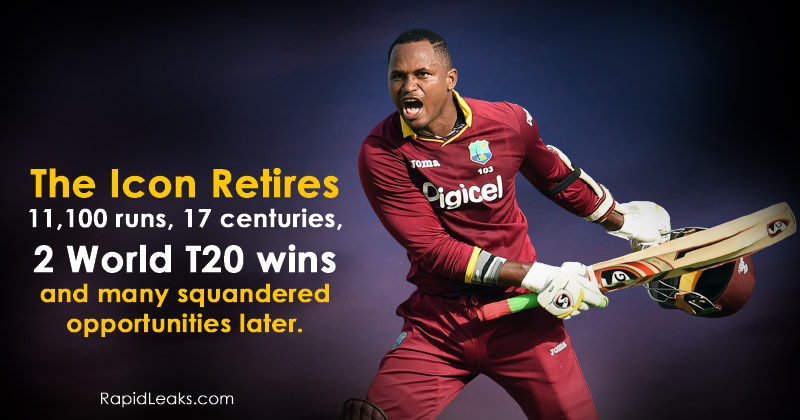

No traffic signal in Kingston, Jamaica has come to a standstill. No cricket legend in the Caribbean has stood up and said nice things. Not even a single post from Cricket’s powerful governing body has offered anything close to an emotional send-off. In an age of social media, where posting the status of one’s early morning nature’s call is yet to become a norm- or who knows- the retirement of a two-time world cup winner, someone recognized as the ‘man-of-the-match’ for playing definitive knocks in 2012, 2016 World T20 editions hasn’t generated an iota of sadness or warmth.

On the contrary, there may even be a sense of gladness that Marlon Nathaniel Samuels has moved on.

Can only beckon a question. Who’s at fault? Rather, whose loss is it anyway?

Much before T20 cricket became the norm and the West Indies, the two-time ODI World cup-winners established their insignia on the sport’s favorite format, Marlon Samuels had made a place for himself in the national team.

A team for whom he’d play, sometimes very gritty (108 not out off 75 vs India, 7th ODI at Vijaywada in 2002), at times, utterly ballsy (260 v Bangladesh, including 31 fours, off 455 deliveries, 2nd Test at Khulna) and on other occasions, strangely uninspiring knocks, such as a gamut of performances in 2005 (in Tests) and 2006 (in ODIs), where despite playing for half a decade he averaged under 19 in both formats.

As Marlon Samuels departs, a two-time world cup-winner, someone who powered more sixes in T20Is for West Indies (69) than Andre Russell (42), Darren Sammy (31), and DJ Bravo (50)- the usual strongmen for West Indies and scored over 11,000 international runs (54 half-centuries and 17 centuries), the cricket world must debate a subject on which we are yet to find a satisfactory or fulfilling answer.

Should overwhelming criticism necessarily follow a proven match-winner who may not necessarily have been a team player?

And if not, then should the likes of Kevin Pietersen, 13,000 international runs, 33 centuries, Test avg over 47, not to forget an Ashes-hero be only condemned in that they often seemed moody or their own people when the team was playing to a different beat?

Truth be told, it’s interesting that Marlon Samuels’ retirement holds the power to open a Pandora’s box of beliefs and ideologies associated with the model decorum of a cricketer.

But the sad part, one notes is that not many are willing to take up a case, forget defend one of Cricket’s strange characters, who was as gifted as rude on the cricket field, as dangerous to the white-ball as he was to the norms that bind cricket as a team sport.

Samuels authored two of the most widely recognized match-winning innings in cricket’s most exciting format (as some call it) first through a 56-ball-78 (6 sixes) against Sri Lanka in the World T20 (2012) finals and later, through a gutsy 85 off just 66 deliveries against England.

On both occasions, he was batting in the sub-continent, that’s proven to be the nadir of many in the game.

On both occasions he took his team over the line when perhaps none may have expected, courting pressure of a very high level.

In the latter, he even managed to stay unbeaten, having arrived when the chips were down- West Indies reduced to 2 for 5 chasing 156 for victory.

Yet, at a time where he may have wanted to simply duck controversy preferring instead to act normal, sport a smile at having played a key role in his team winning a second title, he instead sparked trouble.

Can you ever respect a batsman who lashes out addressing the media with legs stretched on the press conference table, making jibes at a former cricketer who retired a decade ago?

Not that the legend Shane Warne, the subject of Samuels’ vitriol was the sport’s greatest DNA.

But one’s not sure if the behavior of Marlon Samuels- who had done all the hardwork to first rescue the team from a precarious situation until his stand with Carlos Brathwaite did the job- would find a nod of approval from the great Sir Gary Sobers or the likes of Wes Hall.

But then Marlon Samuels was no Rahul Dravid or Tom Hanks: the perennially well-behaved gents whose mere conduct warranted imitation.

The right-hander with a personal ODI best of an unbeaten 133 in the 2015 World Cup never carried a halo of a saint.

On the contrary, Samuels sat out from the game he loved for two full years for his alleged involvement with a Dubai-based bookie, a conduct that has no place in the sport.

At a time where the likes of up and coming Darren Bravo would’ve wanted a bit more guidance from a senior figure, Chanderpaul albeit present in the national set-up but nearing the twilight zone, Samuels sat out for 2009 and 2010.

Who knows how many runs might he have added had he not self-inflicted the blow of watching the game from the sidelines for 730 days?

We’d never know if he would’ve done enough to up his average, which in missing 15 Tests (figuratively speaking, 30 innings) might have looked a lot better than it does at 32 which is after playing 71 Tests.

Yet a thing must be said.

One of West Indies cricket’s most naturally gifted batsmen to have arrived in the post Lara, Hooper era did, at least once, seem utterly resolute: capable of shunning past mediocrity with the bat.

In 2012, his best year in Tests, Samuels didn’t accumulate, but plunder 386 runs from 7 Tests, with a highest score of 260.

But that average of 86 that year wasn’t the only highlight.

That he took Anderson and Broad at their own turf in compiling scores of 31, 86, 117, 76, and 76, respectively earned him much-needed respect.

But was he able to elongate the purple patch and score heavily in the years that followed?

There are no prizes for guessing.

Never again in the four years for which Marlon Samuels walked down the pitch with the unhurried gait did he even average 31. This is when he had 27 more opportunities to do so.

It also highlights Samuels’ appetite- one pointing to humungous run-scoring as also chickening out in the very unexpected instant.

How did a batsman end up owning mediocre numbers in the international level having played the game for over a decade and a half?

Samuels, it ought to be remembered, was drafted into the national team aged just 19.

Kohli debuted at 23, Lara and Samuels’ close-mate and compatriot Gayle at 21, respectively.

That he’s been called selfish, on more occasions than he’d have liked, picture the ODI ton against India in 2014 under Bravo’s captaincy isn’t the only sour point in the Jamaican’s career.

Surely being called for that seemingly banal off-spin action on more than an occasion doesn’t look pretty.

But then had he just played for numbers alone, Marlon Samuels would certainly have changed himself for the better if absolute reformation- seemed impossible.

He would have pleaded to the administrators to allow him another series from which another 83 runs would’ve taken his tally to at least, 4,000 Test runs.

Isn’t it a bit sad that as Marlon Samuels- 345 appearances for West Indies- walks away there aren’t many plaudits but references to a character that perhaps beckons a movie on its own: fifty and more shades of Marlon?

What did he earn by spewing venom on Ben Stokes and even his wife?

Could he have done more, just a bit more to, at least, draw the same affinity and respect that others with the same experience (albeit lesser natural abilities) command?

Think Shoaib Malik.

In Samuels, West Indies had a fearless madman- he waged a lone assault on Malinga in 2012 World Cup when the rest of the team was in the dugout- who knew both extreme tangents- ordinariness and eccentricity.

Yet that he chose to contend with the thin line in between should offer an explanation as to who Marlon Nathaniel Samuels really was.

A gum-chewing ice-cool bloke both faltered and stunned, and also the self-proclaimed ‘icon’ who gave a darn to the world.